How Humble Moss Healed the Wounds of Thousands in World War I

The same extraordinary properties that make this plant an “ecosystem engineer” also helped save human lives

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cf/77/cf77eaa6-5824-4deb-bd1c-238dc517cb11/dbje34.jpg)

The First World War had just begun, and already the wounds were rotting on the battlefield. In the last months of 1914, doctors like Sir. W. Watson Cheyne of the Royal College of Surgeons of England noted with horror the “great prevalence of sepsis,” the potentially life-threatening response triggered by a bad infection. And by December 1915, a British report warned that the thousands of wounded men were threatening to exhaust the material for bandages.

Desperate to get their hands on something sterile that would keep wounds clear of infection, doctors started getting creative. They tried everything from irrigating the wounds with chlorine solutions to creating bandages infused with carbolic acid, formaldehyde or mercury chloride, with varying degrees of success. But in the end, there simply wasn’t enough cotton—a substance that was already in high demand for uniforms and its recently discovered use as an explosive—to go around.

What were the Allied Powers to do? A Scottish surgeon-and-botanist duo had an idea: stuff the wounds full of moss.

Yes, moss, the plant. Also known as sphagnum, peat moss thrives in cold, damp climates like those of the British Isles and northern Germany. Today, this tiny, star-shaped plant is known for its use in horticulture and biofuel, not to mention its starring role in preserving thousands-year-old "bog bodies" like the Tollund Man, which Smithsonian Magazine revisited last month. But humans have also used it for at least 1,000 years to help heal their injuries.

…

In ancient times, Gaelic-Irish sources wrote that warriors in the battle of Clontarf used moss to pack their wounds. Moss was also used by Native Americans, who lined their children’s cradles and carriers with it as a type of natural diaper. It continued to be used sporadically when battles erupted, including during the Napoleonic and Franco-Prussian wars. But it wasn’t until World War I that medical experts realized the plant's full potential.

In the war's early days, eminent botanist Isaac Bayley Balfour and military surgeon Charles Walker Cathcart identified two species in particular that worked best for staunching bleeding and helping wounds heal: S. papillosum and S. palustre, both of which grew in abundance across Scotland, Ireland and England. When the men wrote an article in the “Science and Nature” section of The Scotsman extolling the moss’s medicinal virtues, they noted that it was already widely used in Germany.

But desperate times called for desperate measures. Or, as they wrote: “Fas est et ab hoste doceri”—it is right to be taught even by the enemy.

Field surgeons seemed to agree. Lieutenant-Colonel E.P. Sewell of the General Hospital in Alexandria, Egypt wrote approvingly that, “It is very absorbent, far more than cotton wool, and has remarkable deodorizing power.” Lab experiments around the same time vindicated his observations: Sphagnum moss can hold up to 22 times its own weight in liquid, making it twice as absorptive as cotton.

This remarkable spongelike quality comes from Sphagnum’s cellular structure, says Robin Kimmerer, professor of ecology at SUNY-Environmental Science and Forestry and the author of Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses. “Ninety percent of the cells in a sphagnum plant are dead,” Kimmerer says. “And they’re supposed to be dead. They’re made to be empty so they can be filled with water.” In this case, humans took advantage of that liquid-absorbing capacity to soak up blood, pus and other bodily fluids.

Sphagnum moss also has antiseptic properties. The plant’s cell walls are composed of special sugar molecules that “create an electrochemical halo around all of the cells, and the cell walls end up being negatively charged,” Kimmerer says. “Those negative charges mean that positively charged nutrient ions [like potassium, sodium and calcium] are going to be attracted to the sphagnum.” As the moss soaks up all the negatively charged nutrients in the soil, it releases positively charged ions that make the environment around it acidic.

For bogs, the acidity has remarkable preservative effects—think bog bodies—and keeps the environment limited to highly specialized species that can tolerate such harsh environments. For wounded humans, the result is that sphagnum bandages produce sterile environments by keeping the pH level around the wound low, and inhibiting the growth of bacteria.

As the war raged on, the number of bandages needed skyrocketed, and sphagnum moss provided the raw material for more and more of them. In 1916, the Canadian Red Cross Society in Ontario provided over 1 million dressings, nearly 2 million compresses and 1 million pads for wounded soldiers in Europe, using moss collected from British Columbia, Nova Scotia and other swampy, coastal regions. By 1918, 1 million dressings per month were being sent out of Britain to hospitals on continental Europe, in Egypt and even Mesopotamia.

Communities around the United Kingdom and North America organized outings to collect moss so the demand for bandages could be met. “Moss drives” were announced in local papers, and volunteers included women of all ages and children. One organizer in the United Kingdom instructed volunteers to “fill the sacks only about three-quarter full, drag them to the nearest hard ground, and then dance on them to extract the larger percentage of water.”

At Longshaw Lodge in Derbyshire, England, the nurses who tended convalescing soldiers trooped out to the damp grounds to collect moss for their wounds. And as botanist P.G. Ayres writes, sphagnum was just as popular on the other side of the battle lines. “Germany was more active than any of the Allies in utilizing Sphagnum … the bogs of north-eastern Germany and Bavaria provided seemingly inexhaustible supplies. Civilians and even Allied prisoners of war were conscripted to gather the moss.”

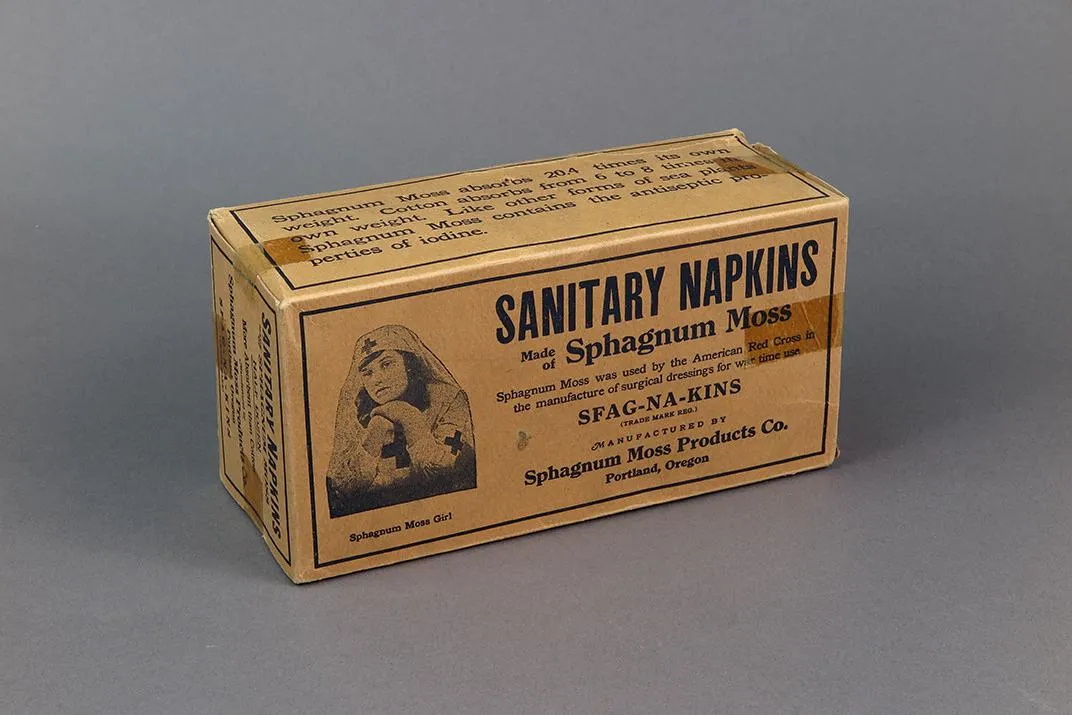

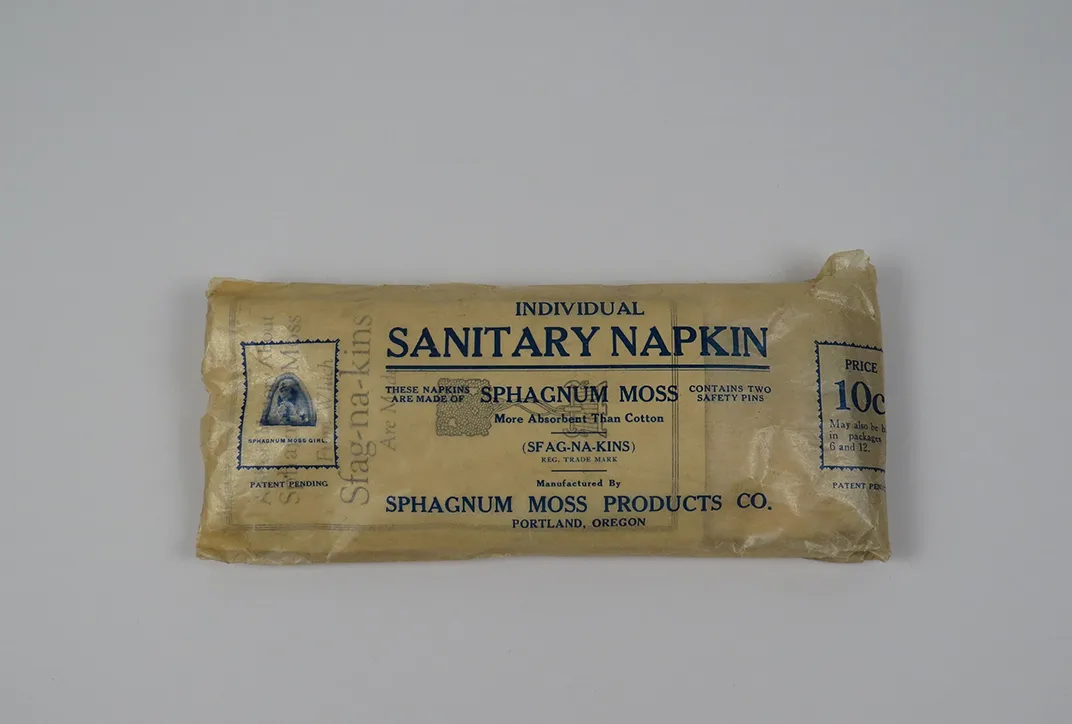

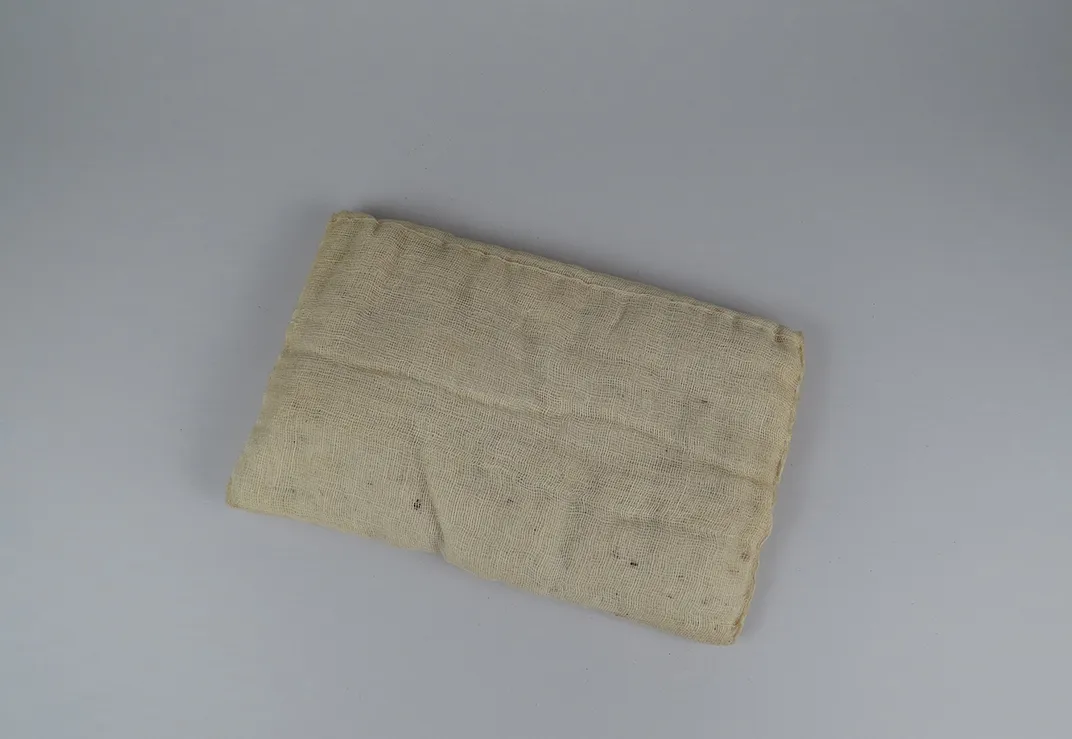

Each country had its own method for making the bandages, with the British stations filling bags loosely while the American Red Cross provided precise instructions for how to layer the moss with nonabsorbent cotton and gauze. “[The British style] seems to have been looked down upon by the American Red Cross,” says Rachel Anderson, a project assistant in the division of medicine and science at the National Museum of American History who studied the museum’s collection of sphagnum bandages. “The criticism was that you were getting redistribution of the moss during shipment and use.”

But everyone agreed on one thing: moss bandages worked. Their absorbency was remarkable. They didn’t mildew. And from the Allies’ perspective, they were a renewable resource that would grow back without much difficulty. “So long as the peat underneath [the living moss] was not disturbed, the peat is going to keep acting like a sponge, so it enables regrowth of Sphagnum,” says Kimmerer. However, “I can imagine if there were bogs that people used very regularly for harvesting there could be a trampling effect.”

So why aren’t we still using moss bandages today? In part, because the immense amount of labor required to collect it, Anderson says (although manufacturers in the U.S. experimented with using the moss for sanitary napkins called Sfag-Na-Kins).

That’s a good thing, because the real value of this plant goes far beyond bandages. Peatlands full of spaghnum and other mosses spend thousands of years accumulating carbon in their underground layers. If they defrost or dry out, we risk that carbon leaking out into the atmosphere. And while humans are no longer picking them for bandages, scientists fear that bogs and swamplands could be drained or negatively impacted by agriculture and industry, or the peat will be used for biofuel.

Besides their role in global climate change, peatlands are rich ecosystems in their own right, boasting rare species like carnivorous plants. “The same things that make sphagnum amazing for bandages are what enable it to be an ecosystem engineer, because it can create bogs,” Kimmerer says. “Sphagnum and peatlands are really important pockets of biodiversity.” Even if we no longer require moss’s assistance with our scrapes and lacerations, we should still respect and preserve the rare habitats it creates.

Editor's Note, May 1, 2017: This article originally stated that peat moss releases protons (it releases positively charged ions, known as cations). It also featured a photo of a non-Spaghnum moss species.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)